THK: What motivated you to go into neuroscience broadly?

RR: As an undergraduate and master's student, I studied children's cognitive and linguistic development. I worked in a couple of labs collecting various behavioral measures of infants' and children's language development, but I became fascinated by what was going on "under the hood," so I chose to focus on neural development for my PhD.

THK: What motivated you to go into your particular area of research?

RR: I started my career as a speech language pathologist, because I believe that language and communication are fundamental components of our humanity and I wanted to help ensure that every child had access to communication. Perhaps because I am so dreadful at learning new languages, I have always been fascinated in how children largely learn language -- most do so effortlessly, soaking it up from their environment, yet some struggle for a variety of reasons. Trying to understand what drives these individual differences (both the biological and experiential mechanisms) is what drives my research. I think starting off in a clinical field is what drives me to make sure my research has applied value, even when answering basic questions about development.

THK: How would you describe your research to a non-scientist?

RR: I study how children learn to talk and communicate with the people around them, and how their brains develop to support these language abilities. Importantly, I am interested in what makes each child's language development unique, and specifically how their developmental trajectories are shaped by their early experiences, such as their interactions with caregivers and society. I try to understand what drives inequities in cognitive and academic development and test ways to improve outcomes for children from diverse backgrounds.

THK: What have been some of the highlights of your career? What is your most proud scientific accomplishment?

RR: While accomplishments are great, the thing that makes me proudest is the perseverance it took to get to those achievements -- the things you don't really hear about. For example, my most cited/popular paper was desk-rejected 3 times before it even went out for review (my current record is 6 rejections for one of my favourite papers -- a study that took 10 years to complete!). I have the most incredible tenure-track job that I love, but it took two years on the market and >40 applications to get there. I'm super grateful and proud of the research funding I have received, but you should see my overflowing folder of rejected grants -- my first major one actually got a worse score on revision, and was only funded because of an extremely lucky break. Every highlight of my career has come on the heels of multiple failures, but that is what makes me the proudest. I wish we all talked more about this!

THK: What motivates, inspires, drives you?

RR: My lab team members! Their passion, tenacity, and sheer brilliance are so inspiring. The future of our field is so bright!

THK: What challenges have or do you face in research?

RR: Personally, my biggest challenge has been figuring out how to balance a demanding and often relentless career with physical, mental, and emotional health (spoiler alert -- I haven't figured it out yet 🙂 Professionally, my biggest challenge is balancing the activities I find personally rewarding (like mentoring & activism) vs. the ones that matter on paper.

THK: What general challenges do you see for science in the upcoming years and what approaches would you say are most important in this regard?

RR: As human subjects research continues to recognize the importance of representation and inclusion, it must employ inclusive practices like community engagement and participatory research. This is tough because many of us weren't trained in these techniques, so we need to listen and relearn. I believe these approaches are essential, but the process is often slow and usually not rewarded or acknowledged. I think the paradigm is starting to shift, but it will be an ongoing process.

THK: What do you think are the most pressing issues in the developmental cognitive neuroscience field for your area of interest? For the field in general?

RR: As our tools continue to improve, I'm really excited to see more and more neuroscience research taking place out of the lab and in the "real world." I think this kind of field-based research is so promising for increasing the ecological validity of our work, and in turn, its translational efficacy. While this requires all sorts of innovation and creativity, it's super exciting for our field!

THK: What do you think is the future of developmental cognitive developmental neuroscience?

RR: I think it is continued integration in multiple ways -- across methods, across ages, across theories and approaches. This is when some really cool stuff happens!

THK: Do you have any advice you’d like to share with the trainees in our community who are interested in pursuing developmental cognitive neuroscience research?

RR: Celebrate the process rather than the outcome. Academia is full of really long term goals -- 5+ year degree, years to finish a study, and even more years to get them published. Celebrating the many steps along the way not only makes it more manageable, but also guarantees something to celebrate when the outcome is ultimately uncertain. And celebrating rejections is a part of that! We share and celebrate both wins and fails in our lab, because both are part of a forward trajectory.

THK: Do you have any advice or key takeaways from your research that you’d like to share with the broader community?

RR: Our most robust finding is that meaningful interaction with caregivers (not sheer input!) is one of the most important factors supporting children's language and cognitive development, even in the face of other adversities. We do a lot of outreach with families, and parents often ask us how to best support their children's future academic development. We tell them that brain building starts early, that they are their children's first and most important teacher, and that they already have all the skills they need -- talk, read, sing, play, and love.

THK: What do you do for fun outside the lab?

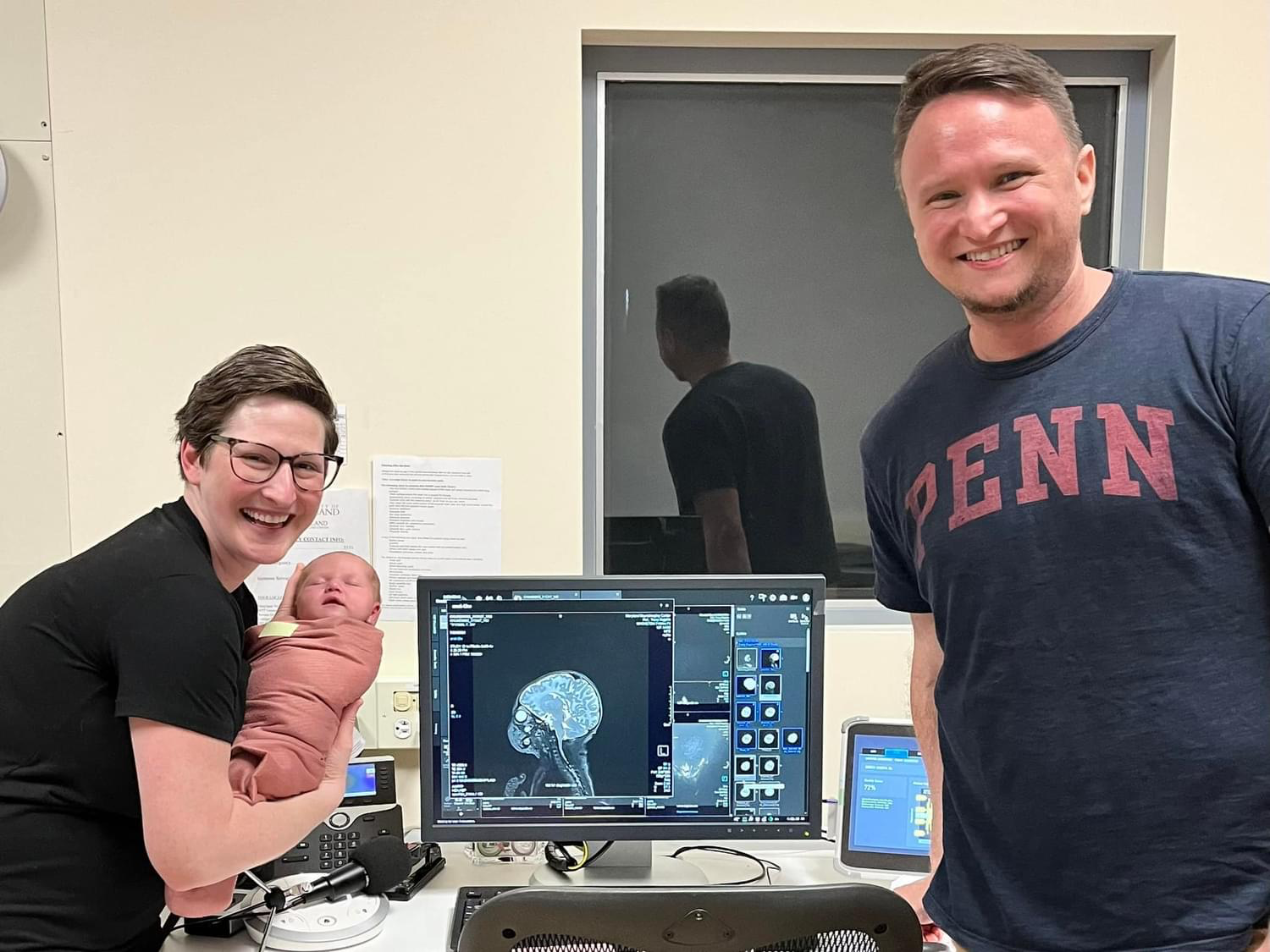

RR: These days I have a newborn, so most of my time is spent with her! After researching development for 15 years, it's so amazing to get to watch it up close in my own personal case study! Besides that, I love travel and eating new foods, hiking, and B-horror movies 🙂

Rachel, her newborn, and her husband, enjoying a brain scan.

Article written by: